INFINITY TURBINE | SALES | DESIGN | DEVELOPMENT | ANALYSIS CONSULTING

TEL: +1-608-238-6001 (Chicago Time Zone )

Email: greg@infinityturbine.com

ElectraTherm 125 kWe ORC and Hurst Boiler For Sale | Biomass and Waste Heat to Energy This pre-packaged 40-foot container combines a 125 kWe Organic Rankine Cycle generator with an industrial Hurst boiler to deliver grid-ready electricity from heat that would otherwise be wasted. With minimal runtime and turnkey integration, this mobile energy platform enables rapid deployment for biomass systems, industrial facilities, and distributed power projects where reliable on-site generation is required. More Info

IT1000 Supercritical CO2 Gas Turbine Generator Silent Prime Power 1 MW (natural gas, solar thermal, thermal battery heat) ... More Info

Supercritical CO2 Turbine TDK Technology Development Kit Use our base tech and make your own IP for Data Center Prime Power Generators using Natural Gas or using Waste Heat... More Info

ORC and Products Index Infinity Turbine ORC Index... More Info

|

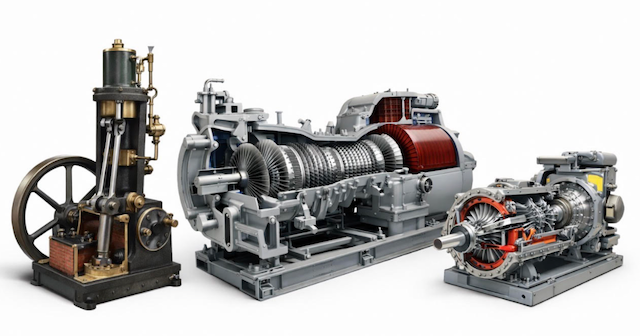

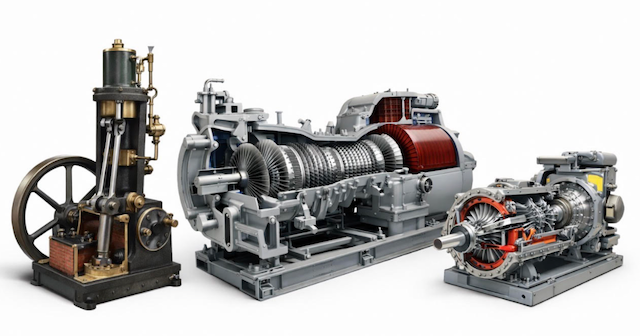

The Evolution of Power Generation From Steam Engines to Supercritical CO2 Turbines From the steam engines that powered the Industrial Revolution to the steam turbines that built the modern electrical grid, thermal power generation has continuously evolved toward higher efficiency and lower losses. This article traces that progression and explains why supercritical CO2 turbines represent the next logical step in energy technology and the foundation of Infinity Turbine’s future development strategy.IntroductionModern power generation is the result of more than two centuries of continuous thermodynamic evolution. Each major step forward in energy conversion has been driven by the same fundamental objective: extract more useful work from heat while reducing cost, complexity, and losses. This article traces that evolution from early steam engines, to high efficiency steam turbines, and finally to supercritical CO2 Brayton cycle systems. It concludes by explaining why Infinity Turbine has selected supercritical CO2 as its primary development path for the future of energy production.Phase One: The Steam Engine EraMechanical Expansion as the First BreakthroughThe steam engine was the first widely deployed machine capable of converting thermal energy into mechanical work at scale. Early designs relied on reciprocating pistons driven by low pressure steam produced in coal fired boilers. These engines powered factories, pumps, ships, and locomotives and formed the foundation of the Industrial Revolution.Performance CharacteristicsSteam engines were mechanically simple but thermodynamically inefficient. Typical efficiencies ranged from 2 percent in early atmospheric engines to roughly 6 to 10 percent in the most advanced compound and triple expansion designs. Heat rates commonly exceeded 40,000 BTU per kilowatt hour.Fundamental LimitationsThe steam engine suffered from several intrinsic constraints: Large heat losses during condensation Mechanical friction from pistons and valve gear Low operating pressures and temperatures Poor scalability for electricity generationThese limitations made steam engines unsuitable for the emerging electrical grid, creating the need for a fundamentally different approach. Phase Two: The Steam Turbine and the Rankine CycleContinuous Flow and Electrical GenerationThe steam turbine replaced reciprocating motion with continuous rotary expansion. This innovation dramatically reduced mechanical losses and enabled direct coupling to electrical generators. The Rankine cycle, based on boiling water into steam, expanding it through turbine stages, and condensing it back to liquid, became the dominant power generation architecture of the 20th century.Maturity and Peak PerformanceBy the late 20th century, steam turbine technology had reached its practical limit with ultra supercritical power plants operating at pressures above 25 MPa and temperatures near 620 C.Key performance metrics: Net efficiency of 42 to 45 percent Heat rates as low as 7,600 BTU per kilowatt hour Unit sizes exceeding 1,000 megawattsThese remain the most efficient steam only power plants ever built.Structural Constraints of SteamDespite decades of optimization, steam turbines face unavoidable thermodynamic barriers: Large latent heat losses during condensation Dependence on massive cooling systems and water supply Metallurgical limits at high temperature and pressure Large footprint and long construction timelinesAt this point in history, steam reached its asymptotic ceiling. Further gains required abandoning phase change entirely. Phase Three: Gas Turbines and the Brayton CycleTemperature as the Primary LeverGas turbines introduced the Brayton cycle, where efficiency increases primarily with temperature rather than pressure. By burning fuel directly in compressed air, gas turbines achieved much higher firing temperatures than steam boilers.In combined cycle configurations, gas turbines achieved the highest commercial efficiencies ever recorded, exceeding 60 percent.Limitations of Open Cycle SystemsDespite their success, gas turbines introduced new constraints: Massive air intake and exhaust requirements Sensitivity to ambient temperature, altitude, and air quality Complex emissions control systems Long lead times and high maintenance at extreme temperaturesThese limitations become especially problematic in modular, distributed, and harsh environment applications. Phase Four: Supercritical CO2 Brayton Cycle SystemsA Closed Loop Thermodynamic ShiftSupercritical CO2 systems retain the Brayton cycle but replace air with dense carbon dioxide above its critical point. In this state, CO2 behaves like a compressible fluid with gas like expansion properties and liquid like density.This produces a fundamental efficiency advantage: compression work drops dramatically near the critical point, while turbine power density increases.Key Advantages Over Steam and GasSupercritical CO2 systems offer: Closed loop operation with no air intake or exhaust Turbomachinery that is 10 to 20 times smaller than steam High efficiency at both large and small scales Excellent compatibility with waste heat, nuclear, geothermal, and thermal storage Insensitivity to weather, altitude, dust, and humidityTarget system efficiencies range from 40 to 55 percent depending on heat source temperature, with heat rates competitive with combined cycle plants at far smaller scale. Evolutionary Logic: Why Infinity Turbine Selected Supercritical CO2Design Selection Based on Physics, Not FashionInfinity Turbine approached power generation development as an evolutionary engineering problem rather than a market trend. The question was not which technology was newest, but which cycle best aligns with future energy realities.Those realities include: Increasing importance of waste heat recovery Growth of distributed and modular power systems Data center and industrial thermal loads Limited water availability Demand for rapid deployment and load flexibilitySteam engines were eliminated first due to low efficiency. Steam turbines followed due to scale and water constraints. Open cycle gas turbines were constrained by air dependence and infrastructure.Supercritical CO2 emerged as the only cycle that simultaneously: Increases efficiency with temperature Operates in a sealed environment Scales from kilowatts to tens of megawatts Integrates naturally with heat pumps, thermal storage, and industrial processesA Forward Looking PlatformInfinity Turbine views supercritical CO2 not as a single product, but as a platform technology. It enables: Modular power blocks Hybrid power and cooling systems Integration with data centers and industrial waste heat High efficiency power generation without reliance on massive centralized plantsIn evolutionary terms, supercritical CO2 is not the next steam turbine. It is the replacement for everything steam cannot economically or physically serve. ConclusionThe progression from steam engines to steam turbines to supercritical CO2 reflects a consistent thermodynamic trend: reduce losses, eliminate phase change penalties, increase power density, and simplify system boundaries.Steam engines built industry. Steam turbines built the grid. Supercritical CO2 is positioned to build the next generation of energy systems where heat, power, and cooling converge.Infinity Turbine has chosen supercritical CO2 because it represents the logical endpoint of this evolution, not a deviation from it. |

|

| CONTACT TEL: +1-608-238-6001 (Chicago Time Zone USA) Email: greg@infinityturbine.com | AMP | PDF |